We’ve reported in the past about the Venus Life Finder (VLF) mission, which is currently in the proposal stage but could potentially one day explore the Venusian clouds for signs of life. What exactly that life would look like is anyone’s guess. Therefore, the instrumentation the mission will use to find that life will be critical. Enter Fluid-Screen (FS), a technology developed by a start-up company spun out of Yale by Dr. Monika Weber. It could potentially directly detect life in the Venusian atmosphere – if only it could deal with the sulfuric acid.

FS’s underlying technology is a type known as lab-on-a-chip, which, according to the company’s website, seeks to “replace the 130-year-old Petri dish with a microchip.” It uses a technique called dielectrophoretic (DEP) microbial particle capture – basically, it isolates single-cell organisms by inundating them with electric fields and then capturing them on the electrode.

This has made the technology extraordinarily efficient at detecting bacterial contamination. According to FS’s webpage, it can do so with 99% accuracy in a matter of minutes. That is a dramatic improvement over existing techniques, which typically require cell cultures and time. Lots and lots of time. One potential application is the food and beverage industry, which likes to know sooner rather than later if part of the processing line is contaminated. Another possible application could be astrobiology.

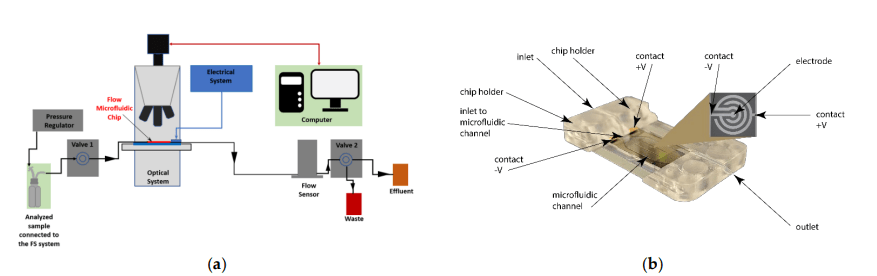

Depiction of the Fluid-Screen system.

Depiction of the Fluid-Screen system.Credit – Weber et al.

As mentioned before, what alien life forms look like is anybody’s guess. But, if they are single-celled, they would probably be subject to the same fundamental forces that make DEP work so well as a detection mechanism for bacteria here on Earth. As such, a space-based version of FS could be useful in helping VLF understand whether there are any life forms on Venus.

To do that, though, it has to be able to withstand the Venusian environment. No easy tasks, considering that even in the cloud themselves, the probes are wholly surrounded by what is believed to be sulfuric acid, which is extraordinarily corrosive to instrumentation. That’s not even considering what life would be like on the planet’s surface.

FS would also have to be capable of being blasted into space in a form factor significantly smaller than its current iteration. While not insurmountable, those two hurdles pose a potential stopping point for its inclusion in the VLF mission, which plans to launch its preliminary mission in 2023 on top of a RocketLab Electron rocket.

UT video on the search for life on VenusThat’s probably too quick for the necessary technology development needed to include FS on the first VLF mission. Still, Dr. Weber, the CEO and inventor of FS, is one of the VLF’s primary team members, so she will be well-dialed into any future development needs of the project.

And as their recent case study points out, there are plenty of other opportunities for using FS on astrobiological missions. Enceladus and Europa are much more accommodating places for FS. Or at least they don’t have as much sulfuric acid.

Either way, new technologies being brought to bear in the search for extraterrestrial life are always welcome. If FS can possibly help contribute to that long-term goal, it deserves all the support it can get.

Learn More:

Weber. et al – Direct In-Situ Capture, Separation and Visualization of Biological Particles with Fluid-Screen in the Context of Venus Life Finder Mission Concept Study

UT – What Would it Take to Find Life on Venus?

UT – A Private Mission to Scan the Cloud Tops of Venus for Evidence of Life

UT – Will Venus finally answer, ‘Are we alone?’

Lead Image:

Depiction of the Venus Life Finder program.

Credit – Seger et al.