We go about our daily lives sheltered under an invisible magnetic field generated deep inside Earth. It forms the magnetosphere, a region dominated by the magnetic field. Without that planetary protection shield, we’d experience harmful cosmic radiation and charged particles from the Sun.

Has Earth always had this deflector shield? Probably so, and the evidence is in old rocks. A team of researchers at University of Oxford and MIT found the earliest evidence for its existence in stones found along the coast of Greenland in a region called the Isua Supercrustal Belt.

Geologists have long known that iron particles in rocks “entrain” a print of the magnetic field that was in place when they formed. So, the research team uncovered rocks that formed some 3.7 billion years ago. It’s not an easy task, according to team lead Claire Nichols of the Department of Earth Sciences at Oxford. “Extracting reliable records from rocks this old is extremely challenging,” Nichols pointed out. “It was really exciting to see primary magnetic signals begin to emerge when we analyzed these samples in the lab. This is a really important step forward as we try and determine the role of the ancient magnetic field when life on Earth was first emerging.”

This 3.7-billion-year-old rock from Greenland. Entrained magnetic field fingerprints help scientists determine that our magnetosphere and magnetic field existed when this rock formed. Courtesy: Claire Nichols.

This 3.7-billion-year-old rock from Greenland. Entrained magnetic field fingerprints help scientists determine that our magnetosphere and magnetic field existed when this rock formed. Courtesy: Claire Nichols.

The team’s samples recorded a magnetic field strength of 15 microteslas at the time they formed. Today, Earth’s field strength is closer to 30 microteslas, so it’s obvious that our magnetic field and magnetosphere have been there for billions of years. It’s also clear that the field changes over time. The science team also found that early Earth’s magnetosphere was amazingly similar to the one it has today.

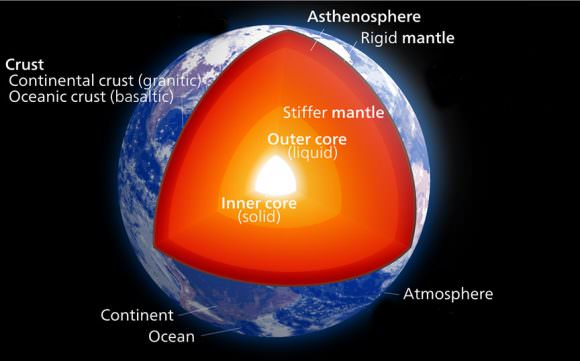

Our planet has a main dynamo at its heart. There are two cores—an inner one and an outer one. Motions in the core regions generate the magnetic field that defines our magnetosphere. Molten iron mixes and moves in the fluid outer core and the inner core solidifies. The two actions together create that dynamo. That’s what’s happening inside our planet today.

This cutaway of planet Earth shows the familiar exterior of air, water and land as well as the interior: from the mantle down to the outer and inner cores. Currents in hot, liquid iron-nickel in the outer core create our planet’s protective but fluctuating magnetic field and magnetosphere. Credit: Kelvinsong / Wikipedia

This cutaway of planet Earth shows the familiar exterior of air, water and land as well as the interior: from the mantle down to the outer and inner cores. Currents in hot, liquid iron-nickel in the outer core create our planet’s protective but fluctuating magnetic field and magnetosphere. Credit: Kelvinsong / Wikipedia

However, when Earth was first forming some 4.5 billion years ago, that solid inner core didn’t exist. Without the interaction we see today between the two parts of the core, it’s hard to know how any early magnetic field existed. That’s an open question among geologists and planetary scientists: how did it form and how was it sustained?

Another question relates to how much the planetary magnetic field has varied over time. Answering that one would help geologists understand just when the solid inner core formed. It would also show how much heat has escaped our planet from deep inside over time. Heat escape drives plate tectonics, which uses large “plates” of rock to shift things around on the surface over hundreds of millions of years.

Rocks have a long and complex history. They form as a molten mixture that solidifies, or in the case of sandstones, are laid down in layers that then harden. In the case of molten rocks, they have magnetic field fingerprints entrained at the time of formation. In measuring those fingerprints, geologists account for any heating that could “reset” the magnetic signatures over time. The Greenland rocks are relatively pristine, meaning they haven’t been significantly heated since they formed. That means their magnetic fingerprints haven’t changed since formation.

Lava cooling after an eruption. This rock has an entrained magnetic field fingerprint from the time it formed. Credit: kalapanaculturaltours.com

Lava cooling after an eruption. This rock has an entrained magnetic field fingerprint from the time it formed. Credit: kalapanaculturaltours.com

Rocks also get weathered by wind, temperature changes and erosion, but the Isuan samples seem to be relatively pristine, according to Benjamin Weiss of MIT. “Northern Isua has the oldest known well-preserved rocks on Earth,” Weiss said. “Not only have they not been significantly heated since 3.7 billion years ago but they have also been scraped clean by the Greenland ice sheet.”

The rocks the team studied date back to the Archean Eon—the second-oldest geologic eon in Earth’s history. That period began about 4 billion years ago, and during that time Earth was largely an ocean world with a limited amount of continental surface. Since then, Earth’s surface has changed a great deal, destroying or burying rocks from earlier times. So, finding rocks that date back that far in time is a big deal.

The Isuan rocks are relatively unchanged since they formed, and bear proof of a magnetic field existing less than a billion years after the planet formed. That same early magnetic field could have played a role in the development of our planet’s atmosphere, by assisting in removing xenon gas. Other old rocks may well tell scientists more about the birth of the magnetic field. There are rocks in Canada, Australia and South Africa that could give unique insight into the formation of the field and its role in making Earth habitable for life.

Researchers Find Oldest Undisputed Evidence of Earth’s Magnetic Field

Possible Eoarchean Records of the Geomagnetic Field Preserved in the Isua Supracrustal Belt, Southern West Greenland