A sleeping giant of a volcano woke up this past week on the Big Island of Hawaii. Mauna Loa, which last erupted in the early 1980s, has been rattling the island with earthquakes for weeks. Finally, on November 27th, the mountain opened up. Not only did residents see this eruption, but NASA and NOAA satellites captured an infrared view of it.

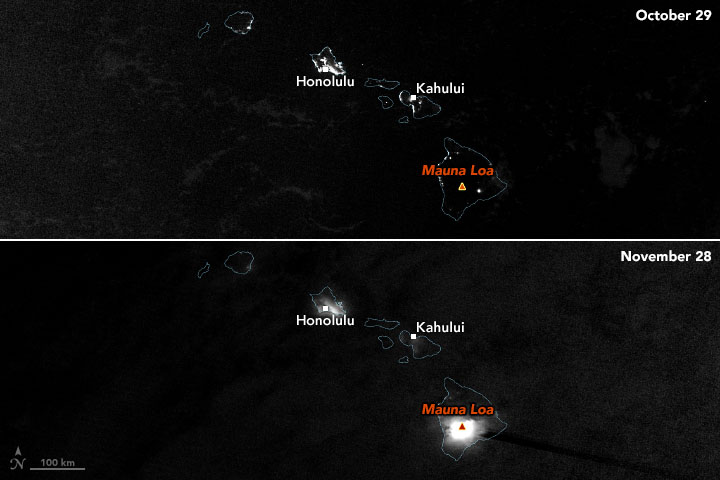

The bright glow of the eruption was visible to NASA and NOAA satellites orbiting hundreds of miles above the surface. The image above was acquired at 2:25 a.m. local time (12:25 UTC) on November 28 by the “day-night band” of the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the NOAA-NASA Suomi NPP satellite. For comparison, the image above shows the same area on October 29, 2022, before the eruption had begun.

The bright glow of the eruption was visible to NASA and NOAA satellites orbiting hundreds of miles above the surface. The image above was acquired at 2:25 a.m. local time (12:25 UTC) on November 28 by the “day-night band” of the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the NOAA-NASA Suomi NPP satellite. For comparison, the image above shows the same area on October 29, 2022, before the eruption had begun.

The first space-based images show the mountain as it appeared on November 28th. By that time, lava flows had started and stopped in the mountain’s caldera, and fissures and vents had opened up. The Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the NOAA-NASA Suomi NPP satellite acquired the first day-night band images (above) at 2:25 a.m. local time (12:25 UTC) on November 28th.

Cloud cover scattered light from the eruption and urban areas and made it look more diffuse. “It also looks like the lava emitted by the eruption was so bright that the sensor was saturated, producing a ‘post-saturation recovery streak’ along the VIIRS scan to the southeast,” noted Simon Carn, a volcanologist at Michigan Tech. “These streaks are only seen over very intense sources of visible radiation.”

The Big Island has several active volcanoes and Mauna Loa is the biggest. It has erupted off and on for thousands of years. Eruptions in the early 1980s sent flows close to the city of Hilo and were visible from atop Mauna Kea. The mountain is a typical shield volcano and rises about four kilometers above sea level. It’s the largest active volcano in the world and covers half the Big Island.

Monitoring Mauna Loa From Space

Geologists constantly study Mauna Loa and other volcanic activity such as the ongoing Kilauea and Pu’u O’o eruptions. Space-based observations provide additional information about how these eruptions affect the atmosphere. “The eruption is effusive rather than explosive, although its initial phase overnight on November 28 was quite energetic and injected some sulfur dioxide to high altitudes, possibly all the way to the tropopause,” said Carn. “That is unusual for this type of eruption.”

In addition to the NASA-NOAA observations, the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-5P satellite detected sulfur dioxide (SO2) from the eruption. Its primary atmospheric sensing instrument is the Tropospheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) sensor. NASA operates the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) on the Aura satellite. Both instruments measured the SO2 levels at about 0.2 teragrams. “These sensors measured within 5 minutes of each other in early afternoon and are in excellent agreement despite having different algorithms,” said Nickolay Krotkov, an atmospheric scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. During Mauna Loa’s 1984 eruption, it emitted about 1.2 teragrams of SO2 over a period of three weeks.

Mauna Loa’s Ongoing Eruption

The ground-based images of the current eruption show lava fountains reaching up nearly 200 feet, with lava flows heading out of at least two active fissures. Mauna Loa lies along a feature called the Northeast Rift Zone, which is the most active area on the island. Kilauea and the Pu’u O’o eruption areas are also located along the rift.

At the moment, the flows have not threatened homes, but they should reach the Saddle Road which cuts through the island in a day or two. Geologists at the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) continue to monitor the flow as well as earthquake activity. Tremors are continuing, which means that the eruption is likely to go on for some time. Prior to the first eruption, an earthquake swarm served as a wake-up call that something was about to happen.

This image taken from the International Gemini Observatory site on Mauna Kea shows the flow from nearby Mauna Loa. It also captured a rare “lava light pillar” caused by a juxtaposition of light from the eruption, high clouds, and cold temperatures that freeze water crystals in the air. Courtesy International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA

This image taken from the International Gemini Observatory site on Mauna Kea shows the flow from nearby Mauna Loa. It also captured a rare “lava light pillar” caused by a juxtaposition of light from the eruption, high clouds, and cold temperatures that freeze water crystals in the air. Courtesy International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA

The Big Island is home to a number of observatories at the summit of Mauna Kea. So far, the eruption has not affected their operations. However, the National Solar Observatory’s Mauna Loa GONG facility lost power as the eruptions began, and lava flows blocked the access road. NSO has shut it down temporarily. GONG is the Global Oscillations Network Group and focuses on the internal structure of the Sun using helioseismology. The eruption also affected access to NOAA’s Mauna Loa Observatory (part of the Global Monitoring Laboratory). NOAA shut it down and suspended its data-gathering operations.

Looking Back Through Time

The Hawaiian islands are part of a chain of Pacific volcanoes created as a tectonic plate moved over a hot spot. They began forming some 70 million years ago, and the Big Island contains the youngest of them, called Kama‘ehuakanaloa (formerly called Loihi). It’s forming underwater off the southeast coast of the Big Island. Currently, six volcanoes are active in the whole island chain, including Haleakala on the island of Maui.

For the current eruption, personnel with NASA’s Disasters program are actively monitoring the eruption and are in the process of providing data and imagery to other agencies, including USGS HVO and FEMA. Space-based sensors can monitor the emissions from the volcano and share that data with affected communities on the island.