What do MINBAR, TARDIS, Cardassian Expansion, BoRG, DS9, Tatooines, and ACBAR all have in common? They’re names of astronomical surveys and software created by astronomers who say that science fiction (SF) influenced their careers. Those names are just one indicator of widespread interest in SF in the science community. It’s not surprising considering how many scientists (and science writers) grew up with the genre.

Planetary scientists Colin Pillinger and John Zarnecki, and cosmologist Stephen Hawking often cited their SF interests. Astrophysicist Carl Sagan famously talked about his fannish admiration of the Edgar Rice Burroughs Mars books on his Cosmos program. Rocket designer Hermann Oberth wrote SF, which caught the eye of astronomer Lyman Spitzer (of Spitzer Space Telescope fame). In addition, there are many scientists who have written creditable SF stories. These include Patrick Moore, Isaac Asimov, David Brin, Vonda McIntyre, and many others who used their science to inform fiction.

Inspiring Science Fiction Characters

It shouldn’t be news to anyone that these “geeky” SF interests remain part of many astronomers’ lives. Or that their interests show up in their work. The science fiction universe does more than entertain—it inspires careers. And, most often, specific characters made a huge difference in an astronomer’s formative years.

Take, for example, the character of Dana Scully in The X-Files. Or the woman who captained a starship in Star Trek: Voyager, Captain Janeway. Or, the characters of Lieutenant Uhura (played by the late Nichelle Nichols), Mr. Spock, Captain Kirk, Dr. McCoy, and Montgomery “Scotty” Scott in early Star Trek. Countless engineers mention Scotty when you ask them about their heroes in SF. There are doctors who admired “Bones” McCoy and Dr. Beverly Crusher as inspirations. There’s even a dentist in Florida who designed offices and treatment rooms with a Trek theme.

Females are quite active in science fiction fandom and many are writers for the genre. A number of women in science mention the female characters Uhura, Scully, and Janeway as role models. Dr. Erin Macdonald, currently science advisor to the Star Trek universe, often cites Scully and Janeway among her mentors. She wrote on Twitter in 2019, “I grew up in Colorado, did my Ph.D. at the University of Glasgow, and would not have become a scientist if it weren’t for Dana Scully and Captain Janeway. Fictional mentors are just as valid.”

Macdonald, whose science career included research into gravitational waves, dedicated her dissertation to Janeway. In an article she did for StarTrek.com, she said Janeway helped her on her path to becoming a scientist. “Eventually, I would finish up at my Colorado undergrad and leave my friends and family behind to pursue a Ph.D. in Scotland. As I embarked on my new adventure, a certain Star Trek captain would emerge as a close companion, mentor, and inspiration. Kate Mulgrew’s portrayal of Captain Janeway on Voyager was everything I needed at that time of transition.”

The Star Trek universe isn’t the only influence scientists mention as their inspiration for STEM careers. Dr. Who, Stargate, Battlestar Galactica, Star Wars (in its many forms), and others come into play. The characters and plots set on distant worlds and in other times excite more than the imagination of budding scientists; they often (as in Macdonald’s case) inspire careers in SF itself.

A Survey of Science Fiction Interests

How many astronomers actually claim influence by SF in its many forms? That’s what astronomer Elizabeth Stanway at the Centre for Exoplanets and Habitability at the University of Warwick in the UK wanted to know. She surveyed colleagues to see how true it was. She got responses from 36 members at her university, and 239 responded during the UK National Astronomy Meeting 2022. Many surveyed were interested in SF, and furthermore, a good majority (69%) said that the genre influenced their career and life choices.

Stanway grouped the survey results into a schematic with five broad regions of interest labeled. They were: the asymptotic SF-lovers branch, the astronomers’ main sequence, the weakly interacting Cloud, the SFH (Science Fiction Haters) cooling track, and the D clump. Since a clear majority of the astronomers surveyed expressed a love of the genre, they became the basis of what she called the “astronomers main sequence”.

SF Finds Its Way into Science

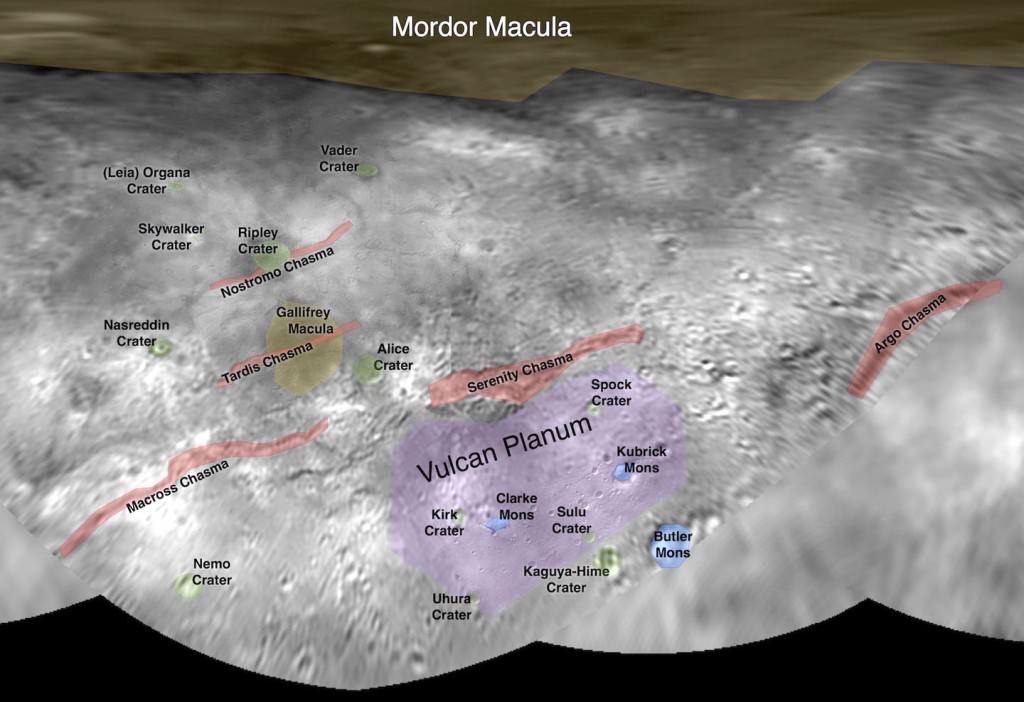

So, those acronyms at the top of this story that Stanway reported in her paper? They’re part of a much larger collection of SF-related monickers that show up in scientific literature. And, on other planets. Scientists on various missions have named rocks on Mars after SF characters, and during the New Horizons mission, some features on Charon got informal names such as Mount Spock, Vulcan Planum, Serenity Chasma, Ripley Crater, Clarke Mons, and Nemo Crater.

This image contains the initial, informal names used by the New Horizons team for the features on Pluto’s largest moon, Charon. Most of these names were approved by the IAU, including Clarke Montes (Clarke Mons), Kubrick Mons, and Spock Crater. NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

This image contains the initial, informal names used by the New Horizons team for the features on Pluto’s largest moon, Charon. Most of these names were approved by the IAU, including Clarke Montes (Clarke Mons), Kubrick Mons, and Spock Crater. NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

In her paper, Stanway shares a table of some of the more colorful references taken from SF that she found. For example, MINBAR comes from Babylon 5, and stands for the Multi-INstrument Burst ARchive—a collection of data about stellar explosions. TARDIS is a supernova open source modeling code, while BoRG is a survey called Brightest of Reionization epoch Galaxies, named for the alien race that terrorized Star Trek crews.

Tatooines is one of the more intriguing names, used to describe circumbinary planets. It’s short for The Attempt To Observe Outer-planets In Non-single-stellar Environments and is a survey program using radial velocities to search out these worlds. ACBAR is a Star Warsian-related name for the Arcminute Cosmology Bolometer Array Receiver, which is a photon trap and references the famous line from the movie’s Admiral Ackbar, “It’s a trap!”

Stanway concludes her look at SF interests among scientists with suggestions for more surveys of astronomers and other scientists. Those could assess how deeply SF is woven into their interests and careers. She also points out other areas that need to be studied, in particular the gender differences and other personal aspects that influence interest in the genre and science careers.