Everyone loves looking at the Moon, especially through a telescope. To see those dark and light patches scattered across its surface brings about a sense of awe and wonder to anyone who looks up at the night sky. While our Moon might be geologically dead today, it was much more active billions of years ago when it first formed as hot lava blanketed hundreds of thousands of square kilometers of the Moon’s surface in hot lava. These lava flows are responsible for the dark patches we see when we look at the Moon, which are called mare, translated as “seas”, and are remnants of a far more active past.

In a recent study published in The Planetary Science Journal, research from University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder) suggests that volcanoes active billions of years ago may have left another lasting impact on the lunar surface: sheets of ice that dot the Moon’s poles and, in some places, could measure dozens or even hundreds of meters (or feet) thick.

Scientists believe that the moon’s snakelike Schroeter’s Valley was created by lava flowing over the surface. (Credit: NASA Johnson)

Scientists believe that the moon’s snakelike Schroeter’s Valley was created by lava flowing over the surface. (Credit: NASA Johnson)

“We envision it as a frost on the Moon that built up over time,” said Andrew Wilcoski, lead author of the new study and a graduate student in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences (APS) and the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at CU Boulder.

The researchers used computer models to try to recreate conditions on the Moon long before complex life arose on Earth. They discovered that ancient moon volcanoes spewed huge amounts of water vapor, which then settled onto the surface—forming stores of ice that may still be hiding in lunar craters. If any humans had been alive at the time, they may even have seen a sliver of that frost near the border between day and night on the Moon’s surface.

The new study adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that the Moon may be awash in a lot more water than scientists once believed. In a 2020 study, Hayne and his colleagues estimated that nearly ~40,000 square kilometers (~25,000 square miles) of the lunar surface could be capable of trapping and hanging onto ice—mostly near the Moon’s north and south poles. However, where all the water came from is still unclear.

It’s a potential bounty for future moon explorers who will need water to drink and process into rocket fuel, said study co-author Paul Hayne, who is also an assistant professor in APS and LASP.

What Hayne is inferring with rocket fuel is that future astronauts on the Moon could do what is known as electrolysis of water, as water consists of the molecule H20, or two hydrogen atoms for every oxygen atom. Electrolysis is the process of using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. While oxygen can be used for breathing, the hydrogen can be used for fuel for return trips to Earth or even to venture farther out into the solar system.

As stated, it is hypothesized that most of the trapped ice is near the Moon’s north and south poles. This is because the moon’s axial tilt is only 1.5 degrees, compared to the Earth’s axial tilt of 23.5 degrees. As a result, there are craters in both the north and south poles of the Moon that might receive constant sunlight or none at all. This could mean that ice might be present within craters in what’s known as permanently shadowed regions (PSRs), which are designated as areas near the north or south poles of the Moon that never receive direct sunlight and are thus extremely cold (-248°C to -203°C; -415°F to -334°F).

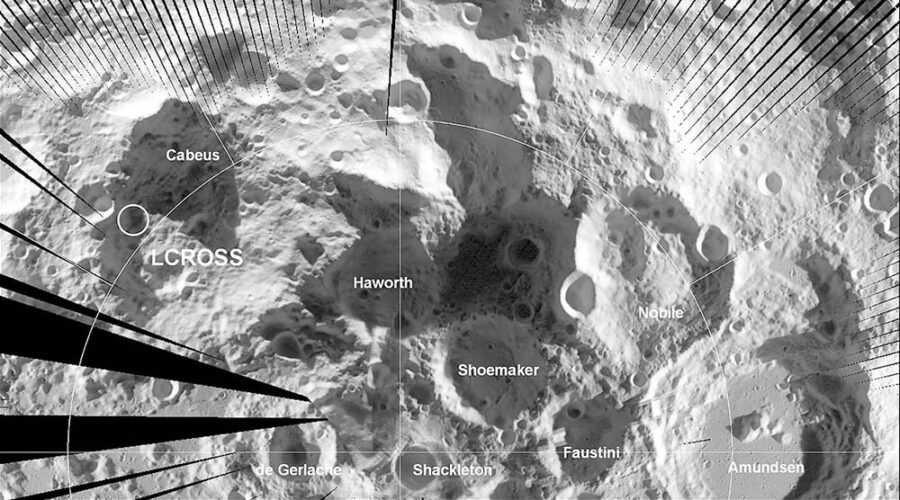

One crater of interest is Shackleton Crater located at the lunar south pole. Shackleton 21 km (13 mi) in diameter and 4.2 km (2.6 mi) deep. What makes Shackleton so intriguing is that while its rim is almost entirely bathed in permanent sunlight, the inside of the crater is permanently shadowed, leaving open the possibility for ice deposits to be present deep within the crater itself. Several missions from three space-faring nations have examined Shackleton using cameras, radar, sensors, and even physically smashed by an impactor, all in hopes of learning it literal dark secrets.

The Diviner instrument aboard the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter imaged the temperatures of the south polar region, shown here. (Credit: NASA)

The Diviner instrument aboard the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter imaged the temperatures of the south polar region, shown here. (Credit: NASA)

All of this research regarding water on the Moon is in preparation for the eventual return of humans to the lunar surface, which has been devoid of us Earthlings since Apollo 17 in 1972. These incredible missions belong to NASA’s Artemis program, which aims to land the first woman and person of color on the surface of our nearest celestial neighbor. Using as much ice on the Moon as possible will mean astronauts won’t have to rely as much on Earth for resupplies, which can be very expensive.

How much ice is on the Moon? How much ice is within Shackleton Crater? Will we be able to utilize this ice for future astronauts in lunar settlements? Only time will tell, and this is why we science!

As always, keep doing science & keep looking up!

Sources: The Planetary Science Journal, Nature Astronomy, US Department of Energy, Space.com, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera, Science, Sky & Telescope, NASA